Manga and anime, Japanese comics and cartoons, span cultures and provide a bridge between past and present. Education, particularly international education, accomplishes the same thing.

In January, Assistant Professor of Sociology Kazuyo Kubo and Assistant Professor of Animation and Motion Media Brandon Strathmann are leading the travel course “Transgenerational Identities in Japan: The Role of Anime and Manga.”

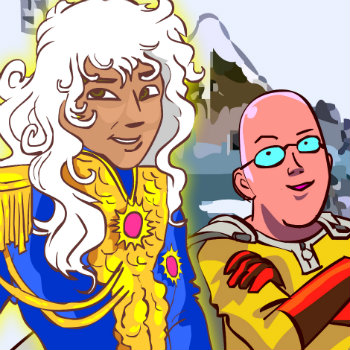

Professors Kazuyo Kubo and Brandon Strathmann (illustrated

here by Strathmann) will teach a course in Japan.

Dr. Kubo says the course taps into the cultural-observation skills needed both by artists and social scientists to “produce socially responsible work.”

“The students in this travel course will explore observational methods in order to paint pictures of people’s lives,” Kubo says. She calls it “creating a narrative of what you see.”

This is part of what helps the travel course build another bridge, one between Lesley schools, in this case the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, in which Kubo teaches, and the College of Art and Design, where Strathmann teaches.

“This class uses the observational and analytical skills of sociology to greatly enhance the abilities of visual artists to absorb the cultural meaning of the behaviors and social structure of foreign cultures,” says Strathmann, whose career has included work at Pixar and for the “Family Guy” cartoon.

The course, he adds, “also investigates the aesthetic principles of Japanese art and how it profoundly influences the animation art of the West.”

While the “Transformers” movie franchise, “Street Fighter” and video games have obvious antecedents in manga and anime, the very rise of the “graphic novel” art from — essentially, longer comic books for literate adults — originated in Japan. According to author and comics expert Francisca Goldsmith, America’s earliest graphic novels are rooted in the “underground comics” movement of the 1970s, though the art form had been flourishing in Japan since after World War II. Today, many American graphic novels feature beloved superheroes, while others tackle complex social issues, including racism, gender identity and politics.

And the roots of manga go even deeper, Strathmann points out.

“Manga is a very old cultural phenomenon in Japan,” he says. The Choju-jinbutsu-giga “Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans” is a set of four picture schools often referred to as the ‘first manga.’”

He explains that the artwork takes real moments of life in 12th-century Japan and transforms them into comical fantasy.

“Monks and peasants are depicted as a mix of frogs, monkeys and rabbits,” Strathmann explains. Ceremonies and gatherings are interrupted by slapstick comedy … (with animal antics) “similar to DreamWorks’ “Kung Fu Panda.”

“Transgenerational Identities” explores Japan’s unique aesthetics that reflect the country’s ancient traditions, present-day industry and technology, and futuristic visions that inform Japan’s “visual culture.”

“Samurai Castles, mega-cities, shrines and temples will teach students about the social and spiritual life of the Japanese,” Strathmann says. “While many manga include cyborgs and other futuristic inventions, they mingle with traditional Kami or Yokai (spirits and phantoms) from Japanese mythology. There is not a distinct line between the eras in Japan, just as many Japanese participate in a variety of traditions and rituals from many religions, with no sense of spiritual conflict.”

A digital alteration of a Katushika Hokusai painting, by Brandon Strathmann.

During the course, Strathmann says, students will travel see a number of festivals in Osaka, journey to many areas of central Japan to visit culturally important sites and explore manga and anime museums, vast stationery stores and other locations to “fuel students’ creative endeavors with a greater understanding of the imagery and narrative arising from the lives of Japanese artists.”

And just as Porter and Harvard Square haunts provide ample opportunity for people-watching, students in the Osaka course can learn much about Japanese culture simply from hunkering down in a restaurant or bar, Kubo indicated. By focusing on the mundane — inspecting menus and observing how people place their orders for food and interact with employees — students can draw inferences about what they’re seeing, arrive at conclusions and start to develop an accurate picture of a culture foreign to them. Then they can turn those observations into art.

“We will be making artwork inspired by the people and places we experience during our studies in this country,” Strathmann says. “Participants will maintain a journal of their reflections along with life drawings of locations and people.”

But the lesson doesn’t stop there, Kubo says.

“Some students may expect to learn abut Japanese society and Japanese people,” she says. “But what they may also experience is discovery of self as a result of constantly encountering something unfamiliar.”