Diana Nyad works harder. Where most headliners in Lesley University’s Boston Speakers Series stand behind a podium and regale audiences with anecdotes, Diana Nyad prowls the edge of the stage, a tow-headed panther punctuating her tales of triumph with strides from one end of the stage to the other.

Wearing a headset microphone and a black suit, the famed long-distance swimmer pantomimes the strokes that propelled her from Cuba to Key West, Fla., in 2013. She is the only one to have swum that expanse without the aid of a shark cage. She sings, speaks in foreign tongues and does impressions of both her parents and others, mimicking their accents.

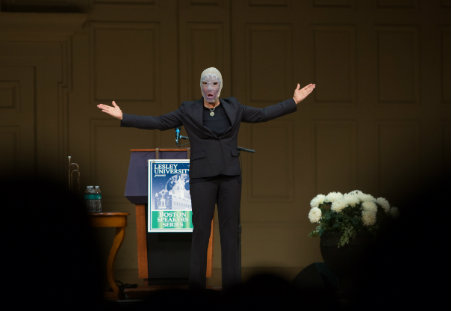

Diana Nyad dons the mask that protected her from jellyfish stings,

but was "hell on earth" to wear.

She blows “Reveille” on a bugle.

“Don’t sleep in,” she exhorts. “Don’t miss anything.”

A tale of triumph

For 90 minutes, Nyad captivated the crowd in Boston Symphony Hall, mixing humor with thrilling recollections of her time in the water, both as a child with Olympic dreams and as an adult embarking on a legendary quest she could never give up on.

She swam to fame first in 1975, circumnavigating Manhattan through the less-than-pristine East and Harlem rivers. (“I did finish with a monstrous eye infection.”) Other long-distance swims in tropical waters added to her acclaim, but it was her 2013 swim from Cuba to Florida, at 64 years old, that cemented her legend.

But, had sports fans known her as a child, they would have seen it coming.

Nyad’s father, of Greek and Egyptian heritage, instilled in her a love of the ocean, which he compared to a Rembrandt painting. He also taught her to cherish her family name, a homophone of the ancient Greek mythological nymphs of the water, which would signal her destiny.

“I was 5 years old. I didn’t even know what a destiny was,” she quipped.

A few years later, her French-born mother would indicate Cuba on the horizon, across from their Fort Lauderdale home. “It’s almost so close, you could swim there,” Nyad said in an exaggerated French accent, imitating her mother.

Without realizing it, the seeds of Nyad’s lifelong journey were planted.

As a teenager, amid her single-minded pursuit of racing excellence (“I didn’t even smoke pot in the high school parking lot: That’s how deep the sacrifices went.”), a peer taught her to focus on her lunula, the half-moon at the base of her fingernail, as a reminder to put every last bit of effort into chasing her dream.

When her parents objected to what they viewed as fanaticism — early mornings in the pool, 1,000 sit-ups each night, blond hair turned green by chlorine — she replied, “That’s how people get ahead, Dad: they’re fanatics.”

One of those fanatics, tennis superstar Billie Jean King, approached Wimbledon’s Centre Court “like a cheetah on the hunt,” Nyad said, explaining that “the first Zen athlete” didn’t focus on her opponent, she played “the fuzz on the tennis ball.” King’s tenacity allowed her to brandish the Wimbledon trophy 20 times. King left an impression on the young Nyad.

While Nyad’s training habits might have made her a difficult daughter and sibling at times, the arduous repetition and the “never give up” attitude kept her alive during her attempted oceanic crossings between Cuba and the United States. The swim is 100 miles due north on the map, but much longer in reality, thanks to a due east Gulf Stream that drags swimmers and mariners off course, and an opposing, incessant wind that agitates the ocean, creating perilous peaks.

“A sport of masochists,” she referred to it wryly, and with more than a hint of pride. A sport that requires training swims of 15 hours, followed by swims of 16 hours, then 17.

A sea of troubles

In addition to the sheer magnitude of the mileage, Nyad’s headline-grabbing crossings — even the successful one — were replete with physical and mental dangers. Though she used no shark cage, she was surrounded by a six-kayaker flotilla that kept the marine predators at bay with jabs via electrically charged PVC pipes. But, if the sharks are hungry enough, Nyad warned, they’ll risk the discomfort to their snout’s sonar system.

“Sharks are smart” and know humans aren’t part of their diet, she recalled an expert telling her. “A shark might take a leg, but won’t eat your whole body.”

Somehow, she deadpanned, that knowledge “isn’t very reassuring.”

Worse, though, are the box jellyfish.

Diana Nyad plays "Reveille."

“Ninety percent of the people who have been stung by the box have died,” she said. Nyad, though, is in the 10 percent, she maintained, by dint of her will.

While aggressive fish and cold, treacherous waters challenge them, long-distance swimmers are also tormented by their own bodies and minds. Pain and exhaustion are followed by hallucinations like, in Nyad’s experience, the Taj Mahal and the Yellow Brick Road (traversed by the Seven Dwarfs).

To stay focused, she tried to remember the dwarfs’ names. She counted in various languages. Other times she sang “Over the Rainbow.” Bending at the waist, Nyad demonstrated her crawl stroke on stage and beautifully belted out the “Wizard of Oz” showstopper.

When the obstacles weren’t physical or mental, they were geopolitical, owing to the U.S. ban on travel to and from Cuba, a relic of the Cold War only now being discarded by degrees. Her fifth, and ultimately successful, crossing was aided by a surprising addition to her team of shark experts and coach and best friend, Bonnie: then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, whose phone call on Nyad’s behalf blasted through bureaucratic impediments within a day.

“It looks like a solitary sport, but it takes a large team,” Nyad said. It also takes the willingness to, as President Theodore Roosevelt said, “dare greatly.”

After several failed attempts at the swim that beckoned her from childhood, Nyad, then a sports journalist, met and befriended the late actor Christopher Reeve, “Superman,” who became paralyzed after a fall from a horse. During that time, she was growing restless reporting on the feats of other athletes, and had “started to feel the malaise of the spectator.” Reeve told her, “You don’t know what’s coming tomorrow,” and urged her to resume her open ocean quest, and the rest is athletic history.

“Are you the person you admire?” Nyad asked the audience. “What is it you’re doing with this one wild and precious life?”

Since her legendary swim, Nyad has been effectively coaching masses of people via her lectures and motivational speeches, while still serving as an inspiration and friend to others by participating in grueling fundraising swims. But her focus is on a more terrestrial goal today, organizing Herculean walks from Boston to New York and between other major American cities.

“We’re going to make this nation into a nation of walkers,” she said, adding that she’s planning a swimming fundraiser for survivors of the Boston Marathon bombing. She pointed out one of her heroes in the audience, marathon race director Dave McGillivray, an Ironman competitor, and invoked the “Boston Strong” rallying cry.

Nyad was the fifth speaker in the 2015-16 season of Lesley University’s Boston Speakers Series, which continues March 23 with novelist John Irving.