The Mosse family was all but erased by the time Hans Strauch, a Mosse descendent and founder of Boston’s HDS Architecture, first visited Berlin, Germany.

Both of his parents fled Germany in the wake of Nazi rule and shared little of their experiences with their children, once they resettled in America and rebuilt a new life. “We had no idea the extent of our family history in Berlin,” Strauch, chair of our Board of Trustees, said in a lecture held at Lesley’s Washburn Auditorium.

Part of the Strauch-Mosse Visiting Artist Lecture Series, the Oct. 24 event marked the first time its founder had a chance to speak about the origins of his own family and his work rebuilding the Mosse legacy in Germany.

Exodus and return

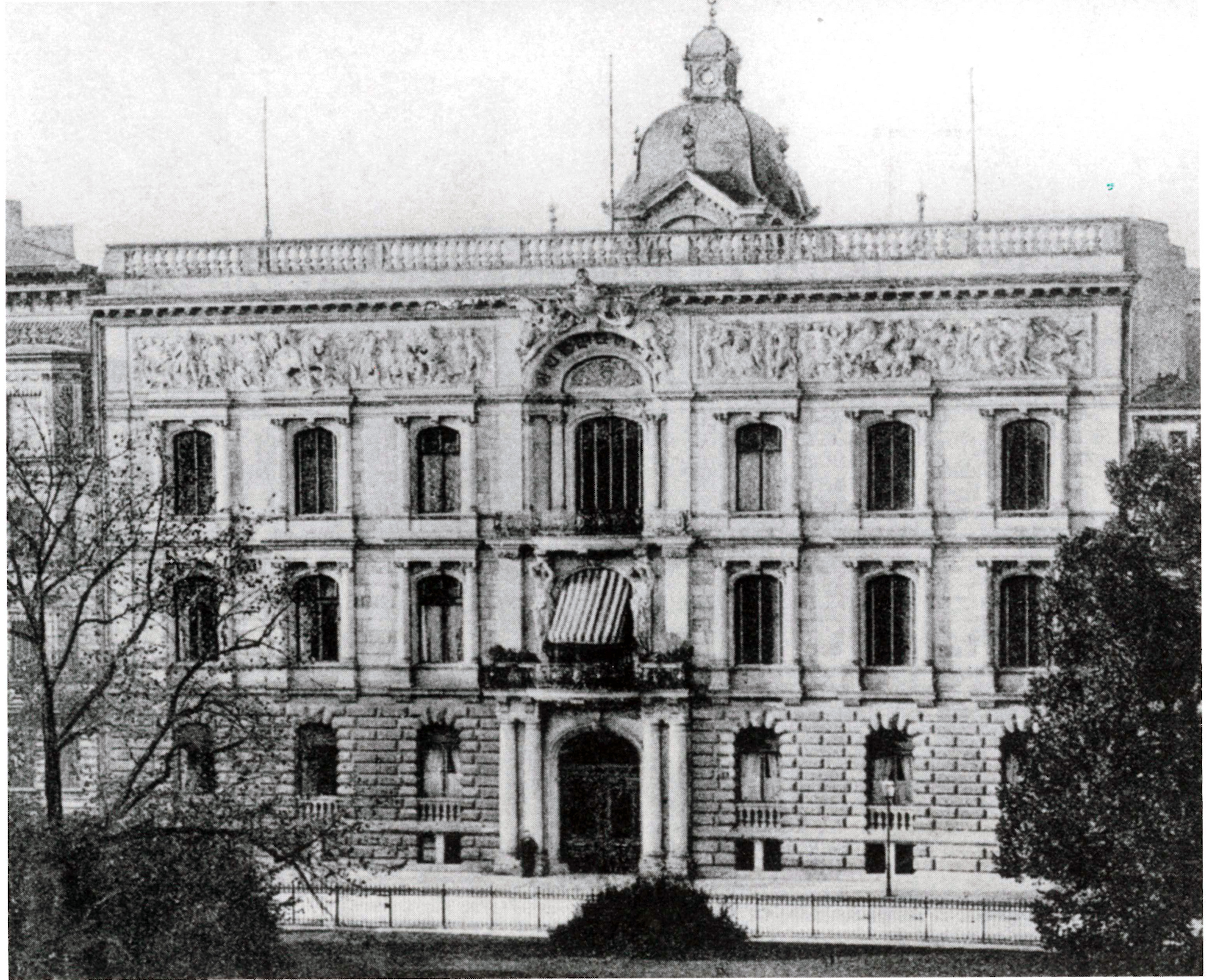

Before World War II, patriarch Rudolph Mosse had built a sizable publishing empire. Known for philanthropy, an extensive art collection and the majestic Mosse Palais in Berlin’s Leipziger Platz. But, after the Mosses’ flagship paper, the Berliner Tageblatt, published anti-Hitler sentiments, the Nazis targeted them.

“The Mosse family became a symbol of the hated Jewish press,” said Straus, who first visited Germany with his brother Roger in 1982.

After the Mosse family fled Germany in 1933, the Nazis auctioned more than 1,000 pieces of the Mosse art collection, and Allied forces attacks destroyed the palais, which was adjacent to Hitler’s Berlin HQ. During the Cold War, the Berlin Wall cut across the Leipziger Platz.

The eventual destruction of the Berlin Wall, however, signaled a new era for the Mosse descendants, whose property was restored in the early 1990s. When developers began making plans to rebuild the iconic buildings along the octagonally shaped Leipziger Platz, Strauch was a natural choice to design the new Mosse Palais, and he did so taking cues from his family history and the city itself.

On walks through East Berlin he saw buildings sprayed with machine gun fire.

“It was as if I was on a stage set,” he recalled.

In the rebuilding process, Strauch admired the city’s efforts to keep its history visible even while moving forward, “giving clues always connecting to the past.”

In designing the palais, he did the same.

“I felt facing the history of the property would be necessary to inform the design,” explained Strauch, who referenced elements of the original building in his design. He also wanted to make sure the structure represented the present and future of both his family and the redeveloping city, with the design drawing the eye from the ground upward to a crown just above the words Mosse Palais.

A place for the palais

When they broke ground in 1995, it was one of the first in the city’s massive restoration plan. The platz remained a virtual no-man’s land, with no other nearby construction besides the palais, though other parts of Berlin were being renewed. The sound of leftover bombs, removed from nearby building sites and detonated outside the city limits, provided both a reminder of the past and a signal of better things to come.

Last year, Strauch celebrated the 20th anniversary of the new Mosse Palais, now in a bustling hub of culture and commerce. In addition to his rebuilding efforts, the Mosse Foundation, started in 1982 by his aunt in Dr. Hilde Mosse and continued by his brother Roger, has worked to recover the family’s artwork.

During his presentation, Strauch showed photos of a reclining lion statue from the palais, which was recovered and installed last summer in the entry hall of Berlin’s James Simon Gallery. Many pieces have proven more difficult to reclaim, including a large bronze statue called “The Three Dancing Maidens,” which once graced the palais’s courtyard. The piece is now owned by a hotel that has been reluctant to return it.

“It’s hard work. It’s very hard work,” said Strauch.

Along with the physical representation of his family’s legacy in the form of the palais, Strauch has sought to resurrect the philanthropic legacy as well. Lesley is one beneficiary.

Introduced to the university two decades ago, Strauch was struck by the university’s dedication to social justice. A decade ago, he started the biannual lecture series, an idea that originated with then-president and dean, Joseph Moore and Stan Trecker, respectively. The series coincided with the relocation of the Art Institute of Boston, now the Lesley University College of Art and Design, to Cambridge.

“We felt that we needed to do something that would be kinetic, something that would show our commitment to the arts,” Strauch said.

In the past decade, the Strauch-Mosse Visiting Artist Lecture Series has welcomed a wide array of visionaries and artists to Lesley, including famed choreographer Twyla Tharp, human rights photographer Sebastiao Salgado, “Arthur” creator Marc Brown, jazz musician Hugh Masekela, Nobel prize winning poet and playwright Derek Wolcott, Broadway and “Hamilton” star Christopher Jackson, and Pulitzer Prize winner Colson Whitehead, author of “The Underground Railroad.”